Wages, Wages, Wages

Despite strong domestic job creation, wage growth in Australia remains subdued and is part of the reason we believe the RBA’s policy tightening cycle will lag the US.

By contrast, in the US we’re seeing more and more indicators suggesting that wage inflation is accelerating faster than the more widely followed (but lagged) official economic data suggests.

For example, recent NFIB small business surveys showed that 25% of small business owners plan price increases due to rising wage costs and the survey’s indicator of job openings being hard to fill reached the highest level in the history of the series, which dates back to the 1970’s.

The ISM Prices Paid index, which surveys industrial companies on their input costs, is showing similar evidence of labour shortages.

More anecdotally, the Wall Street Journal ran an article this month titled – “How bad is the labor shortage? Cities will pay you to move there.” – which described the lengths smaller towns are having to go to in order to attract workers.

And the advertisement below from a California based burger chain (In-N-Out) has been getting attention in the blogosphere. Even though the company is known for paying very well (store managers can earn $160k per annum), the $16/hr starting wage advertised is 23% higher than what they typically pay and significantly higher than California’s $11/hr minimum wage.

(If you’re visiting California and want to sample their burgers, try ordering one ‘animal style’. Their burgers are good, but not as good as Shake Shack.)

While inflation markets have been more focused on rising oil prices lately, the more important story and the one that has longer lasting effects on inflation, is wages.

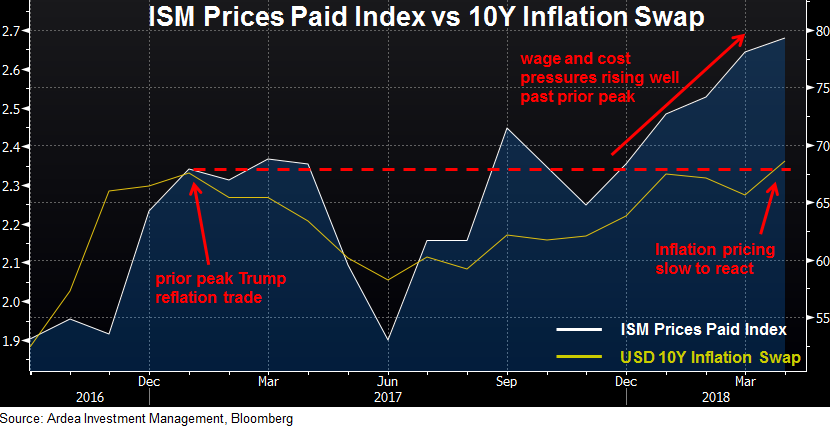

Recall last year, following a period of subdued inflation in 2016, market pricing of inflation expectations spiked higher on President Trump’s election and his promises of pro-growth (and therefore inflationary) policies … the so-called Trump reflation trade.

However, those expectations turned out to be premature as inflation readings subsequently disappointed and President Trump hit obstacles in delivering on his promises. Accordingly, inflation expectations reversed lower and hit a trough in June 2017.

Since then inflation expectations have gradually rebuilt back to those levels, as both growth and inflation indicators have strengthened again. So what’s different this time around?

As the chart below shows, measures of wages and other input costs – proxied by the ISM Prices Paid index – have now risen well beyond where they were at the peak of the Trump reflation trade, yet longer term inflation expectations – proxied by 10 year inflation swaps – have been slower to react.

An attractive way to exploit this pricing inconsistency is via breakeven inflation curve steepeners (refer to – “Better Ways to Position for Future Inflation Surprise” for details).

And remember, although inflation pressures remain subdued in Australia, we are not immune from the feed through effect of higher interest rates, because of the Australian banks’ reliance on USD funding markets.

Ardea Investment Management