Strange behaviour in option markets

(Note: the option terminology used in this discussion is explained at the end of this post on our website)

Finance text books, reams of academic research and practitioner experience all point to the existence of a “volatility risk premium” (VRP), which is a foundational principal of option selling strategies.

For interest rate options as an example, a positive VRP means that implied volatility (i.e. the expected volatility of interest rates as implied by option prices) is higher than realised volatility (i.e. the day to day movements in rates that actually materialise).

Pure volatility focused option selling strategies will profit if future realised volatility turns out to be lower than what is currently implied by option prices. However, unexpectedly large market moves can wipe them out, which is exactly what happened to equity volatility selling strategies in February last year. (Refer – Reuters: investors burned as bets on low market volatility implode)

Given the asymmetric downside risk these strategies face (i.e. modest gains relative to the potential for large losses), it makes sense that they would need to be enticed by a risk premium to engage in option selling activity.

On the other side of this trade, option buyers are willing to pay this risk premium because they are getting insurance like protection against large market movements that could hurt their portfolios.

As with your home insurance, you expect this protection to cost something, while the insurance company needs to earn a positive return for selling it to you. On average, insurance premiums earned (akin to implied volatility) should exceed expected insurance claim payments (akin to realised volatility), resulting in a positive risk premium, or else the insurance company would eventually go out of business … and indeed, history shows that most active option markets display a persistently positive VRP.

When the gap between implied and realised volatility is large, the VRP is large and option sellers have a large safety cushion. The flip side being that option buyers are paying more for protection.

However, just like with any financial market, changing demand-supply dynamics and market inefficiencies can cause these relationships to break down for periods of time, which is exactly what’s happening now in some interest rate option markets.

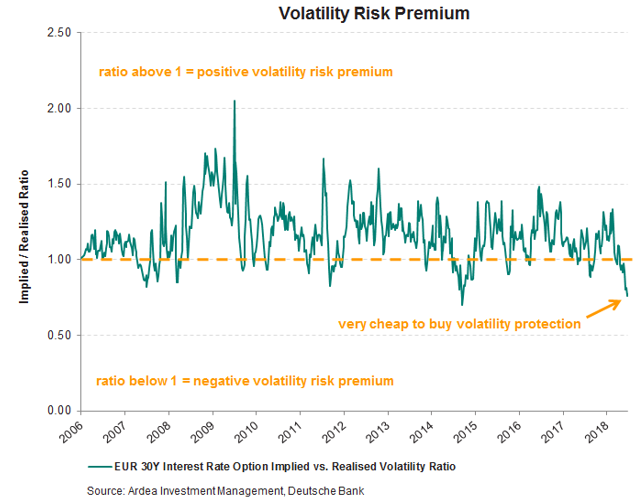

As an example, the chart below shows that the VRP in EUR interest rate options is currently negative because implied volatility is lower than realised (i.e. the ratio of implied to realised is less than 1).

Most of the time the ratio is positive, which is consistent with the existence of a positive risk premium, but recently realised volatility has picked up, while implied volatility has remained near record low levels, resulting in a negative VRP .

The existence of a negative VRP is an unusual situation that makes it very cheap (and profitable) to buy volatility protection using these interest rate options.

Such a strategy can generate modest positive returns even in benign market environments, with the potential for very large gains in volatile environments, when equities and other conventional assets incur losses.

Basically, you’re getting paid to own downside protection.

Why would anyone be willing to sell options at a negative risk premium? Two possible explanations spring to mind;

- Yield Chasing Behaviour

The main side effect of the ultra-low interest rate environment that has defined the post financial crisis era has been the reach for yield.

Yield chasing capital flows, forced to take more and more risk in order to eke out a little extra return, have pushed up asset prices and compressed risk premia across asset classes ranging from equities to credit.

In the options world, volatility selling strategies have become popular as a way to boost returns by earning an up-front payment (i.e. the option premium) in return for taking the low probability but high impact risk of unexpected market volatility causing large losses.

Yield chasing investors may be willing to ignore negative risk premia in option markets because they are more focused on the up-front payment they receive in the belief that the risk of large market moves is too remote to worry about.

- Diversity Of Market Participants

One of the main reasons that fixed income markets exhibit persistent inefficiency in pricing is the diversity of participants, each with varying objectives, constraints and behaviours.

In the options context, some market participants use interest rate options to express bets on the direction of interest rates. For example, a view that interest rates are going lower can be expressed by selling a ‘put option’, which embeds both a directional exposure (known as ‘Delta’) and a volatility exposure (known as ‘Vega’). In this case the investor is more focused on the directionality of the option and the fact that they happen to also be taking on volatility exposure at a negative risk premium is just a side effect of the way they decided to express their bet.

In environments like the current one, where there is a strong consensus expectation that volatility will remain low, investors are more incentivised to express directional views by selling options, even if it means accepting negative risk premia.

Whatever the motivation, volatility selling strategies tend to earn modest positive returns most of the time but can occasionally incur very large, and sometimes terminal, losses.

Notably, prolonged low volatility conditions can create a self-reinforcing feedback loop resulting in yield chasing capital, emboldened by the recent history of low volatility, being enticed into selling more options, which in turn reduces implied volatility and generates profits for these strategies, in turn triggering yet more option selling. This dynamic typically works and works and works … until it doesn’t.

Eventually an external catalyst of some kind creates unexpectedly large market movements, which causes volatility to spike higher, triggering large losses for option sellers.

By contrast, volatility buying (i.e. ‘long volatility’) strategies typically have the opposite return profile and make large profits when volatility surges. Given this will usually be a negative environment for most conventional assets, ‘long volatility’ strategies can be thought of as a form of portfolio insurance.

Normally, these strategies expect to incur small losses in benign low volatility environments, in return for large profits when things go wrong … just like an insurance policy.

However, because of the current unusual environment of negative volatility risk premia this dynamic has flipped, meaning these strategies can generate modest profits even when volatility remains low, while still offering the potential for very large gains if volatility rises.

Continuing the insurance analogy, it’s not just a cheap insurance policy; it’s one that actually pays you to hold it.

This is particularly compelling at a time when more commonly used blunt forms of portfolio insurance, such as interest rate duration, are currently very expensive.

These are the kinds of opportunities we focus on for our investors’ portfolios and in a world where risk pricing is distorted by ultra-low interest rates and unconventional central bank policies, we’re seeing more and more of them.