Hidden liquidity risk in fixed income portfolios

Liquidity is one of those things that doesn’t get much focus until it’s too late.

News this month of Morningstar suspending ratings on a fixed income fund due to illiquid bond holdings, coming on the heels of other high profile fund liquidity issues (see here and here), has heightened investor scrutiny of the true liquidity of underlying investments in funds that claim to be ‘liquid’.

This recent article from Bloomberg News sums up the situation;

“What’s really inside bond funds these days? The answer, for many of them, is more risk than there used to be.

With little fanfare, many traditionally safe investment-grade bond funds have been edging into more complex corners of fixed income. The goal: to eke out returns in today’s low-interest-rate world.

At issue is just how big some of those risks might turn out to be. Of particular concern is whether managers are moving into investments that could prove difficult to sell in the event investors rush for the exits. High-profile problems at several European funds have set nerves on edge and in the U.S. investors will probably need to be more vigilant.”

– Bloomberg News, ‘Bond funds drift into risky debt’, July 2019

In our view, this scrutiny is very much needed and welcome. It’s also something that regulators are paying more attention to;

“Now, with warnings growing louder about the risks money managers have taken with hard-to-trade investments, Wall Street is starting to wonder: Just where will this end?

That question is reverberating across the financial world after the head of the Bank of England warned that funds pushing into a host of risky investments — in some cases, without investors fully understanding the dangers — have been “built on a lie.’’

Then the central banker, Mark Carney, spoke a word few policymakers use lightly: “systemic’’ — central bank-speak for the kind of risks that can cascade through markets, institutions and economies. Some $30 trillion is tied up in difficult-to- trade investments, he noted earlier this year.”

– Bloomberg News, ‘Liquidity and a lie’, June 2019

Liquid investments are those that can be easily sold in sufficient volumes, whenever needed and without incurring punitive transaction costs. Illiquid investments are those that fail to meet these criteria to varying degrees. (Liquidity is a spectrum rather than a binary concept).

The additional return an illiquid asset offers above a comparable investment that’s very similar in all aspects other than liquidity is referred to as the illiquidity risk premium. This is what investors earn explicitly for taking liquidity risk.

Even long-term investors value liquidity in order to maintain flexibility of asset allocation or access to cash and that desire is often highest at times of market stress, when liquidity is most tested. For these reasons liquidity risk always needs to be accounted for when comparing investments.

While there is always a price for bearing liquidity risk, material liquidity risk may not be appropriate for certain portfolios at any price. For example, defensive portfolios where investors expect to be able to redeem their investment at any time and particularly in adverse market conditions.

With interest rates so low, there is growing pressure on investment managers to ‘reach for yield’ by investing in securities that offer higher returns but that can also become illiquid in adverse market environments (e.g. corporate bonds, loans, Residential Mortgage Backed Securities, emerging markets, structured products).

The same Bloomberg article referenced earlier notes;

“The big worry is that the now-troubled European funds that embraced such investments, only to stumble when investors asked for their money back, are just the tip of the iceberg.

Exposure to illiquid assets and poor-quality bonds has crept into funds as managers hunt for whatever returns they can find in today’s low-interest-rate world.”

That’s not to say these investments are bad per se, but rather that their liquidity characteristics need to be well understood by investors in funds that have exposure to them.

On this point, it’s important to appreciate how structural changes in fixed income markets since 2008 have compromised liquidity in some parts of global bond markets. Unfortunately, it’s not always clear during the good times as to how badly liquidity can deteriorate when markets turn.

For example, within the defensive fixed income segment, the common assumption is that investment grade bonds are liquid. While this assumption does still hold for a specific subset of very high quality government bonds, it is no longer true for a growing portion of the corporate bond sector (i.e. bonds issued by companies).

In fact, it’s widely underappreciated just how much corporate bond trading liquidity has deteriorated in the past ten years.

A research paper from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) notes the growing liquidity gap between government bonds (referred to as ‘sovereign’ bonds in the paper) and corporate bonds;

“Market liquidity in most sovereign bond markets has returned to levels comparable to those before the global financial crisis, as suggested by a variety of metrics and feedback from market participants.

There are, however, signs of increased liquidity bifurcation and fragility, with market activity concentrating in the most liquid instruments and deteriorating in the less liquid ones, such as corporate bonds.”

– BIS Committee on the Global Financial System

Unlike exchange traded equities, corporate bonds are traded ‘over the counter’ (OTC), which means liquidity is entirely reliant on banks using their balance sheets to facilitate buying and selling.

For example, when a credit fund needs to sell bonds, perhaps due to outflows, the fund needs to find a bank willing to buy those bonds. The bank then has to warehouse those bonds on its own balance sheet and run the risk that they decline in value before it’s able to recycle them to a different buyer. This type of business, known as ‘market making’, consumes a lot of bank balance sheet capacity when corporate bonds are involved.

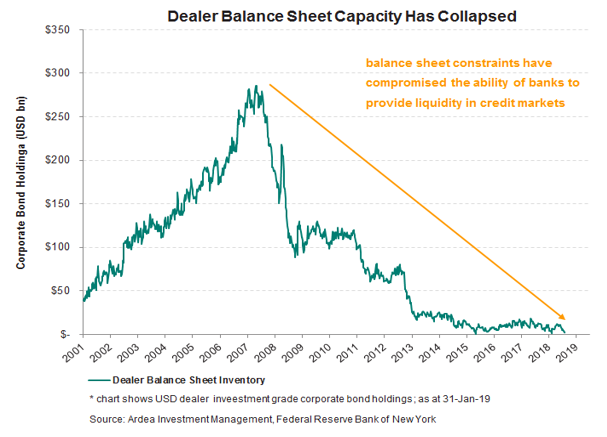

An unfortunate side effect of post 2008 bank regulations, balance sheet constraints and rising cost of capital has been a structural deterioration in corporate bond market liquidity, as banks are now less willing and able to use their remaining scarce balance sheet capacity to support corporate bond trading.

As the chart below shows, the amount of corporate bond inventory that banks are willing to hold has collapsed, which directly compromises liquidity in these markets.

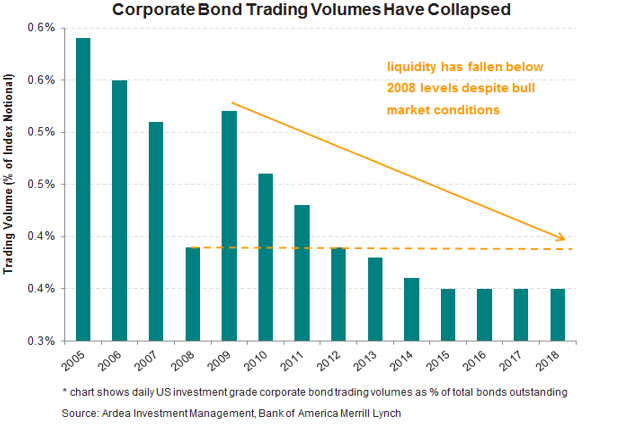

The effect on market liquidity can be seen in the chart below, which shows daily USD investment grade corporate bond trading volumes as a proportion of total market size. The US corporate bond market is the largest and most liquid credit market in the world. Even here, liquidity has consistently declined since 2009.

Regulation has simultaneously decreased the ability of bank balance sheets to hold bond inventories and also increased their cost of capital, leading to structural impairment of market makers’ ability to supply liquidity. These changes are not temporary.

A recent research paper on credit market liquidity from Goldman Sachs concluded the following;

“We provide evidence that liquidity conditions have deteriorated since the crisis – a trend that is captured by four metrics: 1. Lower market turnover; 2. Lower share of block trades; 3. Lower average institutional trade size; 4. Higher price impact estimates of the order flow.

In our view, the deterioration in market liquidity conditions is a major source of vulnerability that investors will need to anticipate and appropriately price … Going forward, we think the value proposition of owning illiquidity is weak, reflecting the more fragile post-crisis market microstructure and the thin level of the corporate bond liquidity premium, in addition to tight valuations.”

– Goldman Sachs, The Credit Line: The Great Liquidity Debate, June 2019

Simply looking at the history of average bid-offer spreads for trades that have taken place, as some liquidity studies do, fails to differentiate between situations where an investor needs to trade and therefore needs a bank to use its balance sheet to provide liquidity (known as a principal trading model) versus where an investor’s interest happens to suit the bank and therefore the bank is simply acting as middleman without taking any risk (known as an agency trading model).

It’s the former that’s needed for true liquidity because investors in a liquid market should be able to trade whenever they want and not only when it suits intermediaries.

On this point, the same research paper from Goldman Sachs notes;

“In our view, the declining sensitivity of bid-ask spreads to market volatility is more indicative of the dealers’ shift away from a principal to an agency trading model, as opposed to improving liquidity. This shift reflects the dealers’ diminished capacity to commit principal capital for sizeable positions.”

A side effect of this liquidity deterioration is increased volatility in corporate bond prices, a small taste of which we got in the fourth quarter 2018 credit market sell off.

A research paper done for US market regulators explained it this way;

“In the past, banks held vast inventories of corporate bonds and traded them regularly, making a profit for themselves and making a market for other investors. This kept price fluctuations in check and was especially valuable in times of stress, as investors could count on banks to play the part of willing buyer when everyone else wanted to sell.

When the global financial crisis erupted in 2008, banks … needed government support to survive. These bailouts came with a price – new rules designed to discourage risk taking and make banks more secure.

The data suggests that these new regulations have challenged banks’ effectiveness when it comes to making markets. While the corporate bond market has roughly doubled in size since late 2007, banks have beaten a hasty retreat from the bond trading business, cutting their inventories by some 75%. As a result, bonds are vulnerable to wider and more violent price swings because the banks aren’t around to keep those fluctuations in check.

The effect has been most pronounced on corporate bonds.”

– US Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC), Playing with Fire: The bond liquidity crunch and what to do about it, March 2016

While it might be tempting to conclude that the rapid first quarter 2019 rebound in credit markets suggests all is well, closer scrutiny says otherwise.

A recent research paper by UBS notes the following;

“The price action of Q4’18 and Q1’19 has been dizzying for credit investors …

These spread changes are major in historical context. Q4 spread widening was in the 90th percentile of historical quarterly spread changes for each market. Q1 has seen a similarly sharp move in the reverse direction.

The worrying aspect of these spread moves is that they are somewhat divorced from the underlying fundamentals that the market is trying to price. Q4’s spread widening did not occur in a recessionary environment, nor even in a period of significant default risk.

Bottom line, we believe the selloffs and rallies of 2015/2016 and 2018/2019 are being exacerbated by a rapidly rising and shrinking liquidity premium. And more importantly, we are concerned that price movements such as these may become the norm going forward.

While investors are concerned primarily about fundamentals, namely high leverage, fallen angel downgrades, and leveraged loan market froth, we believe fundamental and liquidity concerns are inextricably linked and illiquidity risk may be the true amplifier to credit risk in a downturn.”

– UBS, Global Macro Strategy: Market Liquidity, April 2019

The post 2008 regulatory changes have not reduced the risks around corporate bond price volatility and liquidity, they have simply shifted them from bank balance sheets to investors in bond funds.

The only reason this liquidity deterioration hasn’t been more visible is that we’ve been in such a bull market for credit. All the yield chasing inflows have masked this secular deterioration in liquidity. It’s only when those credit inflows turn to outflows that the liquidity problems become visible.

Regulation isn’t the only casual factor here. These dynamics are also driven by structural changes to the ownership of corporate bonds.

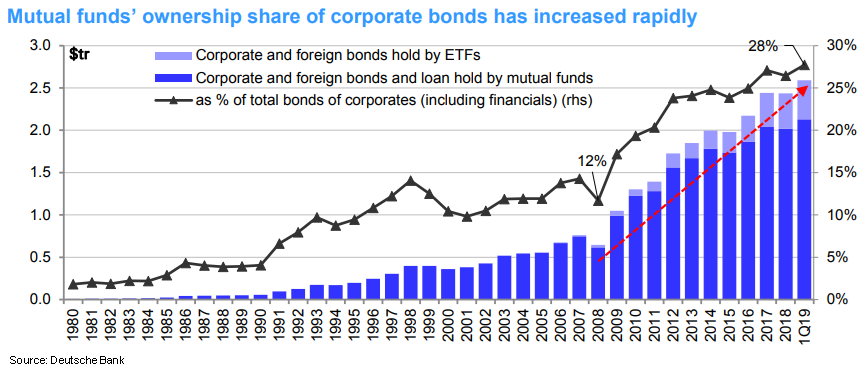

The enormous ‘reach for yield’ that has gripped fixed income markets since 2009 has increased the ownership of corporate bonds in open ended retail investor targeted vehicles like mutual funds and exchange traded funds (ETF’s).

That’s important because these funds (i.e. the ‘buy-side’) are more vulnerable to herding behaviour and rapid investor redemptions in periods of stress … and shrunken bank balance sheets (i.e. the ‘sell-side’) can no longer provide liquidity when the ‘buy-side’ becomes a seller.

A recent research report from Deutsche Bank notes;

“Recent events have been a timely reminder of the potential risks of illiquid securities within open-ended mutual funds offering daily liquidity.

US corporate bonds outstanding have doubled since 2005 with recent issuance running at $1.5trn pa. Over the same period, mutual funds’ ownership of corporate bonds has increased from 12% to almost 30%, or c$2.6trn (refer chart below).

Thus, the ratio of corporate bonds held by mutual funds vs dealer inventory has increased from 2x in 2007 to 43x currently.

In short, the buy-side significantly outweighs the sell-side and the gap has never been bigger.”

– Deutsche Bank, Global Financials: The next liquidity crisis, June 2019

On the same point, the SEC research paper referenced earlier notes the following;

“While banks have been retreating from the bond market, investors have been charging into it. This is a direct result of central banks’ easy money policies: by driving interest rates to record lows, these policies pushed investors – even income starved mom and pop investors – into riskier assets …

The result: large numbers of investors are crowded into the same trades. That causes prices to trend strongly in one direction, but may leave the market vulnerable to a sudden correction if everyone wants to sell at once.

In theory, investors can exit an open ended mutual fund or an ETF at will. But the growing popularity of these funds forces them to invest in an even larger share of less liquid bonds. If everyone wants to exit at once, prices could fall very far, very fast.

A lucky few may get out in time. Others will probably get trampled.”

Corporate bond ETF’s are a particular point of vulnerability because their exchange traded nature attracts investors who expect constant uninterrupted liquidity, which is inconsistent with the growing illiquidity of their underlying investments.

One market commentator described the ETF liquidity mismatch in a recent interview with Barron’s;

“In 2007, the lie was that you could take a cornucopia of crap, package it together, and somehow make it AAA,” she says.

“This time, the lie is that you can take a bunch of bonds that trade by appointment, lump them together in an ETF, and magically make them liquid.”

Sacrificing liquidity in return for additional yield can be a legitimate source of returns if the compensation for illiquidity risk is attractive and investors have the right time horizon of capital.

The problem is that corporate bond markets are no longer offering attractive compensation for growing illiquidity risk and on top of this, large segments of the market (e.g. open ended funds, ETF’s) do not have the right time horizon of capital because investors expect to be able to redeem at any time.

A prudent corporate bond portfolio manager will hold a cash buffer in order to facilitate redemptions, without being forced to sell bond holdings. This works in normal environments but in periods of stress it’s insufficient as they will simply burn through that cash buffer quickly, leaving the remaining investors with an even more illiquid portfolio, which raises complications around the equitable treatment of all investors.

This liquidity mismatch between corporate bond funds’ underlying assets and the liquidity expectations of their investors has consistently grown over the past ten years. As a result, investors who had been reaching for yield in credit markets, thinking all is fine because default rates are low, may be unpleasantly surprised by how illiquid things become when they seek the exit.

In our view, growing illiquidity can become a major pain point for credit markets in coming years, so if you are going to take illiquidity risk, make sure it’s explicitly acknowledged and well compensated.