Global Fixed Income markets: a fragile balance

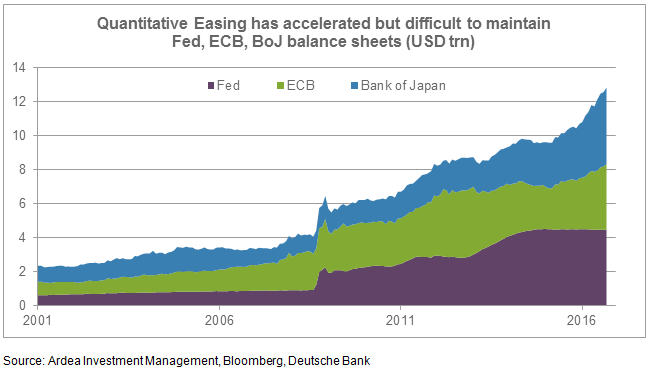

Recently, I returned from a study tour of the world capitals of global macroeconomic policy. This report includes my observations from the road after meeting with key policy making officials, as well as economists and market participants across the US, EU, UK, China and Japan. In short, the current market equilibrium reflects an extremely fragile balance taking place across the global fixed income markets. The US Federal Reserve’s (the “Fed”) efforts to gradually tighten policy will ultimately lead to higher yields, but for the time being they have been overshadowed by efforts from the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of Japan (BoJ) to ramp up stimulus. As a result we have seen lower bond yields over much of this year. However, should the Fed raise rates in December, or if the ECB or BoJ should falter even slightly in their resolve, then fixed income investors need to be prepared for rising bond yields ahead. Fixed income investors will likely have their hands full in managing this transition, but investors should not lose sight of the risks to other asset classes too, as all manner of cash flows will be marked lower in value as discount rates rise.

Fed outlook: tightening in December likely but Yellen happy to be behind the curve

Over the remainder of this year we expect the Fed to incrementally make the case for yet another dovish hike, and deliver on this at the December meeting.

Putting together findings from a large number of meetings in New York, the Fed appears to be comfortable with the pace of the recovery seen so far. This has extended to the point where three FOMC members (Federal Open Market Committee) have expressed dissenting views and supported a rate hike at the September meeting.

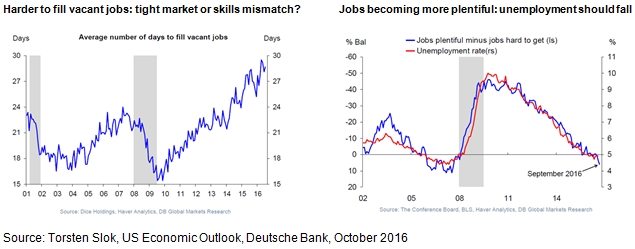

The data picture is such that continued improvement in key labour metrics, and especially wages growth, could paint a sufficiently strong picture by December that the chair has no other choice than to tighten, particularly if it seems that the dissenting minority has become the majority.

Counting against this however is the Yellen’s willingness to “run the economy hot” in the belief that this may bring about a stronger change in inflation expectations, and give confidence that expectations will remain materially above the 2% target. There is also the possibility mentioned in recent comments that a hot economy may have other benefits as well in terms of clearing out any residual sluggishness from the GFC.

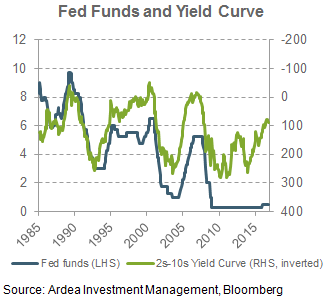

Running deliberately dovish policy settings has been tried before, but rather than the supposed benefits of a hot economy, too dovish policy is more traditionally referred to as being “behind the curve”, reflecting the expectation that overly accommodative policy will have to be taken back more aggressively at some point in future.

In this context it is not surprising that yield curves have been steepening, as the logical consequence of both being behind the curve and/or running the economy hot is ultimately more tightening down the track. Should the willingness to run the economy hot become a more prominent feature of the policy discussion, curves are likely to steepen further.

Estimates of the term premium feed directly into the possibility of steeper curves. The Fed’s own estimates calculated a negative term premium for much of the period following the GFC, as investors pushed government bond yields even lower and below the level that a reasonable path for policy rates would imply. A correction in the term premium back into positive territory (i.e. positive compensation for term risk) would be another factor pressuring curves to steepen.

The main influences preventing such an outcome from occurring right away are the large ongoing bond purchases by the ECB and the BoJ. The crowding out effect of their actions results in many European and Japanese financial institutions, and particularly life insurers, being forced to buy long-term US bonds in order to meet yield targets and match duration.

Recent speculation about whether the ECB or the BoJ might need to taper their purchases is therefore extremely important for the US as well, as it is the main factor driving buying in the long end of the yield curve. This factor is likely to remain supportive for a number of months, but with the ECB and BoJ likely to address questions about the extent of their own policy programs over coming months, they can no longer be viewed as a permanent source of support for global bond yields.

A final consideration for the FOMC is that Yellen’s current term ends in January 2018. A further term would require re-nomination, but there is a view that if she is able to tighten policy twice in 2017 rather than just once, she may feel that she has completed the task of normalising policy, and would see little incentive to accept another term.

UK hunkers down for Brexit while the ECB remains hamstrung by diverging member countries

Discussions in Frankfurt and London were in essence a visit to the old world, with the region as a whole remaining inward-looking and fixated with its own challenges, and largely unaware of the rising economic and financial importance of China.

The logistical challenges around Brexit remain enormous, with significant investment challenges as well. Larger multinationals such as Nissan have stated that they are putting on hold any major investments, unless there is an assurance from the UK government that it will compensate them for any additional costs and barriers from operating in the UK.

The risk of Brexit creating a round of knock-on effects, whereby other countries seek to leave the Euro area or the European Union, appears to have declined. Opinion polls in other EU member states suggested that support for the EU actually increased in the weeks after the Brexit result, perhaps influenced by the dire headlines at the time.

Turning to Europe, the prospects of effective policy from both the ECB and the EU parliament remain heavily constrained by the competing voices at the table – largely Germany versus everyone else. The German view is that there is no secular stagnation and nothing wrong with European growth, with the ECB to blame for keeping rates too low which in turn prevents structural change and creative destruction and allows ever-greening.

In this respect many Germans view the entire policy approach of the ECB as mistaken – the focus of the ECB on delivering credit easing through traditional channels such as bank lending assumes that growth can still be delivered via additional debt, the appetite for which has been greatly diminished. The effects on confidence of negative interest rates are also seen as highly damaging.

Ironically against this backdrop the Germany economy continues to perform well, and on many measures is now at or approaching full capacity. The labour market is tight, and real wage growth is running at 1.5-2% per annum, which is quite high for Germany and at about the level where inflation has begun to kick in the past. The only thing preventing this happening this time around is the more cautious approach of Germany’s labour unions, which have shifted gear to focus more on job preservation, with wage increases now a secondary consideration.

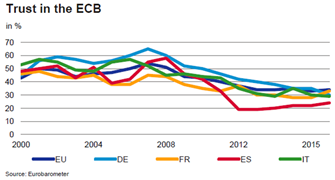

As a result of these developments, trust in the ECB is incredibly low among Germans, and given the reality that politicians tend to respond to their constituents and have a habit of ignoring their own rules and breaking earlier policy commitments, the German voice at the ECB table is likely to remain a vocal one and one opposing any further expansion of stimulus.

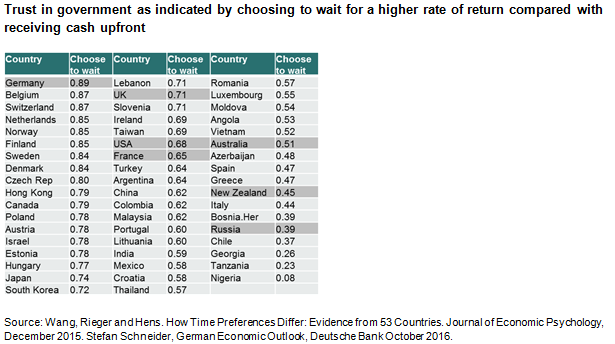

The entire situation is well summed up by recognising that Europe’s member countries, and at the most basic level its people, may ultimately be too diverse to operate effectively as a whole. Research around differing attitudes to the time value of money show enormous variation across the region. When offered the opportunity to take $3800 in one month’s time or $3400 today, national averages show enormous dispersion, ranging from 89% in Germany opting to defer and accept the larger sum in one month’s time, down to 39% in Russia, with relatively even dispersion across Europe’s major nations between these two bounds.

Differing time preferences have been shown to be highly correlated with economic outcomes, such that countries with higher punctuality and even faster walking speeds tend to be more willing to defer payment and wait for higher returns. On the other hand countries that prefer immediate payment tend to have very low trust in government, such as Russia and Italy.

This diversity creates an extremely challenging task for the ECB, and for the governance of Europe more generally.

The ECB itself was upbeat, despite the challenging nature of the environment in which they operate in. Growth outcomes have been ones they have been happy with, although there is a tendency for the ECB to believe that policy has been a material contributor to this outcome, even when it is difficult to be certain that this is the case. As in other advanced economies, persistently soft investment remains a concern.

The ECB outlook for policy is for rates to stay at current levels or lower for a fairly long time. Bond purchases are likely to continue until March or beyond, whichever is necessary. They believe that negative rates have helped through bringing about portfolio capital gains and better credit quality. The ECB acknowledged the concerns for financial sector profitability of a flatter yield curve and negative rates, however unlike the case in Japan, they seem very happy for the banking sector to withstand these costs and there is very little willingness to make concessions. If assets are expensive and banks have to work harder to make loans, then the ECB sees this as being part of the whole point of quantitative easing.

While it remains difficult to be positive on Europe’s fundamentals, the headwinds constraining growth appear to have lessened. Given the years of adjustment already undertaken, there is every chance that economies will manage to deliver ongoing modest growth rates, although genuinely strong economic performance would still require greater adjustment of the region’s high unemployment rates outside of Germany.

China outlook: property boom hits late cycle, while government policy drives households to leverage up

A recent visit to Hong Kong provided the opportunity to hear from a range of China experts, including many specialists and so-called insiders. These included a well-connected public policy professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK), and some experts on the Chinese property and banking sectors.

The outlook over the next 12 months is likely to be shaped by the two competing forces of the property cycle and household leverage. A downturn in property prices seems almost inevitable, but government efforts to cushion the second round effects may be successful in avoiding a more broad-based economic downturn.

For the property cycle, it now appears to be consensus view of those among China that the boom has already peaked, and that developers are now essentially managing downside risk and seeking to finish projects to completion and sell stock as soon as practically possible.

The urgency is compounded by the sense that most residential property projects in China will prove unprofitable if prices move sideways. Even in an upside property price scenario, where prices rise by 30%, as much as 26% of developers’ current projects will still fail to break even. In more modest scenarios where property prices go sideways, most developers will be losing money.

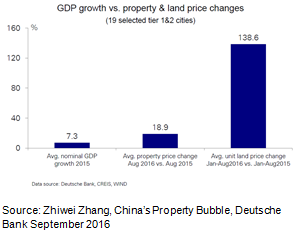

This unenviable assessment reflects the unfortunate combination of an enormous rise in land prices, up by as much as 140%, while finished property prices are up only 20-30% over the past year. Such a large rise in land prices, which are the key input cost, means that developers who have bid up land prices aggressively will now struggle to offload finished projects at a profit.

The key conclusion is that price declines are not needed to trigger a crisis, merely that property prices stop rising.

The implications for commodities, including Australian exports, are likely negative in the short term, although it remains unclear how much this cycle will affect demand for commodities, given the substantial cumulative increase in the size of China’s economy over the past five years.

Longer term urbanisation trends also have some way to go and may still provide some buffer to the cyclical downturn. Reports suggest that there are still as much as 50% of China’s population living in older, pre-1990s housing stock, often provided to employees of state-owned enterprises. More junior employees in particular may still be relying on shared bathrooms and in some cases shared kitchen facilities. So at a very simplistic level, when as many as 600m Chinese may still share a bathroom, the scope for ongoing modernisation of the housing stock and associated demand for commodities is still significant.

China’s property sector also affects profitability in its banking system, with concerns that China’s credit-led growth model may prove difficult to sustain. Current estimates suggest that to maintain GDP growth at 6.5%, China needs to achieve credit growth of 13-14% each year, which given China’s scale is the equivalent of adding an Australia and a Japan each year.

Such a model creates considerable risks for the sector, but does not necessarily mean that Non-Performing Loan’s (NPL’s) will rise. Arrears in China are far more likely to be managed via NPV (net present value) haircuts, essentially extending the maturity of loans by large amounts, and/or lowering coupons. In this sense there is far greater risk of Japan-style stagnation than of a sharp rise in bad debts.

All of this is taking place against a backdrop of considerable change in government policy, and in recent months the authorities have continued their efforts to see the household sector leverage up in China in order to assist efforts to slow growth in corporate debt and encourage corporate deleveraging. China’s corporate sector has among the highest debt levels in the world, yet with the household sector essentially unleveraged, there is considerable scope for a rebalancing of debt across the economy. Efforts to deliberately increase household debt tend to have a track record of ending badly, but this may be the lesser of two evils compared to continuing to run extraordinarily high corporate debt.

Politically speaking, Xi Xinping’s grip on power seems well entrenched. His anti-corruption drive has been effective in marginalising the competing Shanghai faction of the Party, while he has also done much to limit the influence of older leaders of the Party who had appointed him on the mistaken belief that he would be a compliant leader over whom they could continue to retain some influence.

Gauging the outlook for China with any degree of certainty still remains difficult, however for the time being it would seem likely that the property cycle will weaken further, with households and rising consumption able to counter only part of the impact on overall economic growth. Official forecasts by their very nature will continue to be met amid strong desires to keep the economy ticking over, but it now appears clear that genuine underlying economic growth is more likely in the range of 5-6% than above 6%.

Japan outlook: Bank of Japan opens the door for unconstrained fiscal stimulus

A recent visit to Hong Kong and Japan provided the opportunity to hear from a number of different analysts and “insiders” on Japanese policy.

The recent moves by the Bank of Japan to implement a yield curve control policy framework, and crucially the introduction of a target level for 10-year JGB yields, are seen as laying the groundwork for unconstrained fiscal stimulus from the government.

Under the new framework the BoJ will buy as many government bonds as required in order to ensure the 10-year yield remains at 0%. By targeting a fixed level of yields, the Bank is no longer able to set the quantity of buying it will do, as it must simply buy as much as is required in order to hit the target.

Importantly, the Bank would also stop buying if market yields were below 0%, on the basis that buying would take the market yield further away from target. This has been taken by some to indicate a potential tapering of policy, in the event that the buying required to keep yields at target ends up being less than the amount of buying under Quantitative Easing (QE). At best this is merely a tapering in name only however, as even if the Bank is buying less bonds, yields would still remain at low levels.

The other aspect of the new BoJ policy is that by keeping cash rates negative, a zero yield target results in an incrementally steeper yield curve. This is seen as important for the health of the banking sector. The BoJ has apparently come under intense lobbying pressure from the banking sector in recent months, and with the new framework has effectively ceded to their concerns. This creates the interesting outcome of a major macro policy framework being implemented largely for reasons related to the profitability of a single sector, and one which is not even part of the real economy.

What is most interesting about the new framework is that it effectively hands the key to the government to undertake unlimited fiscal stimulus. With yields at zero, and the BoJ ready to continue bond buying to keep them there, it is now possible for the government to embark on fiscal expansion without having concern as to the impact on existing bond holders or on future market pricing. Whether the government steps up remains to be seen, and current talk of fiscal packages is rather small in scale. However, as a step towards ultimately integrating the BoJ balance sheet with that of the central government, the move towards a yield target is a significant one.

Conclusions

Taking into account the rising imbalance present in global fixed income markets, in our view the safest course for fixed income investors remains a defensive one. We now appear to have reached the point where bad news is no longer automatically met with a sharp decline in bond yields, and the recent focus on inflation and efforts around the world to restart fiscal stimulus have awakened investors to the two-way risk present in bond markets. With current low yields offering little compensation for such risk, our focus remains on preserving capital value in preparedness for better yields ahead. In the meantime, such turmoil continues to present a number of attractive opportunities to add value without taking large amounts of market risk, and we continue to access these opportunities as fund and client guidelines permit.

Tamar Hamlyn

Portfolio Manager, Macroeconomics