The drivers of conventional fixed income returns

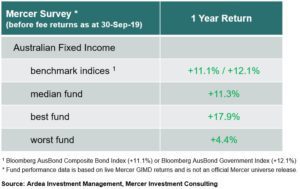

Bond markets have delivered great returns over the past year, a backdrop against which any conventional bond portfolio should have produced strong positive performance, and this is in fact what most fund performance surveys show.

For example, the regular survey conducted by the investment consulting firm Mercer shows strong average performance across bond funds. However, the survey also shows considerable dispersion amongst the funds that make up the average.

Notably, despite strong absolute positive returns across the board, the median manager has actually underperformed the bond market after fees.

At the individual fund level, headline return numbers alone are not informative because they tell you nothing about how those returns were generated. Crucially, they tell you nothing about the amount or types of risks being taken to generate those returns.

For example, some funds in the Mercer survey were skewed toward longer dated government bonds and therefore were taking a lot of interest rate risk to generate returns, while others were more focused on shorted dated corporate bonds and therefore took less interest rate risk but more credit risk.

Therefore, to properly assess fixed income performance it is important to understand the underlying drivers of return and by extension, the types of risk to which a portfolio is exposed. Without this understanding, it is impossible to assess how a fixed income investment might perform in different market environments.

Conventional fixed income investing is largely based on accumulating portfolios of bonds to harvest yield. In return for that yield, the portfolio will be exposed to some combination of interest rate, credit and liquidity risks. The relevant considerations then are whether the risks being taken are adequately compensated and how those risks might impact future performance in different market environments.

What is yield?

Ignoring technical nuances, yield – often referred to as running yield or yield to maturity – represents the return from holding a bond, assuming the bond price remains unchanged. It comprises the interest income paid by the bond plus any discount or premium embedded in the bond purchase price.

For example, a bond issued with a face value of $100 and an interest rate of 5% p.a. will deliver annual interest income of $5 (i.e. $100 face value x 5%). Assuming the bond was purchased for $100, the bond yield is 5% (i.e. $5 income ÷ $100 purchase price). If that same bond was purchased at a discount to its $100 face value, the yield would be higher.

For example, if the same bond was purchased for $95, it would still deliver annual interest income of $5 because interest is calculated based on the bond’s original face value. However, because the investor only paid $95 rather than $100, the yield is now 5.3% rather than 5% (i.e. $5 interest income ÷ $95 purchase price). The yield would be lower if the bond was purchased for a higher price.

A big driver of bond yields is the base line level of interest rates in an economy, as set by a central bank. The exact mechanisms by which interest rate fluctuations transfer to bond yields is beyond the scope of this article, so we will use the terms interchangeably.

Assuming bond prices don’t fluctuate much, and bond issuers don’t default, bond yields can be a reasonable guide to a conventional bond portfolio’s expected future returns. This is why conventional bond funds routinely disclose their average portfolio yield. (Note that when bond prices as volatile, yield can be a very misleading indicator of return potential as explained here)

The benefit of this conventional yield-based approach to bond investing is that it’s easy to understand and investors can use the portfolio yield as a reference point to form their return expectations. However, the drawback is that when bond yields are very low, as they are today, a conventional yield-based approach can get stuck with low returns.

To escape this low yield morass, a conventional fixed income investing approach has three options to increase returns:

- Take more interest rate risk

- Take more credit risk

- Take more liquidity risk

Each of these sources of conventional fixed income risk and return are discussed below.

What is interest rate risk?

Interest rate duration is the key concept here, as it measures the sensitivity of a bond’s price to changes in interest rates (or bond yields).

Duration risk stems from the fact that a bond investor makes a payment today in exchange for a series of future interest payments. At the time of purchase, the bond’s price reflects the present value of that future stream of interest payments, which are fixed in advance. However, the next day if the general level of market interest rates (or bond yields) rises, that fixed stream of interest payments is no longer as valuable, as it is now below current market rates. Therefore the bond needs to be discounted to attract new buyers, and the bond price drops accordingly. The opposite happens when bond yields fall.

The longer dated the bond (i.e. longer duration), the more future interest payments need to be discounted and therefore the more pronounced this effect. Hence, duration measures the sensitivity of a bond’s price to those fluctuations.

As an example, the bond indices referenced in the Mercer survey above comprise a large number of individual bonds, each with their own interest rate duration risk, which is averaged to calculate the index duration. As the individual bond yields fluctuate, their prices move, causing the index value to also move. In the case of the AusBond Composite index, which has a duration of c. 5.5, if average bond yields fall by 1%, the index value increases by 5.5%, and vice versa if yields rise.

Longer dated bonds carry more duration risk because their prices are more sensitive to changes in yield than shorter dated bonds. For example, a 10-year Australian government bond has a duration of 8.8 vs. a 3-year bond’s duration of 2.9, which makes the former 3 times more sensitive to interest rate movements than the latter.

A fixed income portfolio can therefore take more duration risk by holding a larger proportion of longer dated bonds. There are then two mechanisms by which increasing duration may increase the returns of a conventional fixed income portfolio:

1. Higher yields

Bond yield curves are typically upward sloping, meaning longer dated bonds offer higher yields. Therefore the yield of a portfolio can be increased by holding a higher proportion of longer dated bonds.

However, many yield curves around the world are currently quite flat (or even inverted), meaning even long dated bonds that carry a lot of duration risk don’t offer much higher yields. (details here)

2. Price movement

More duration exposure means more sensitivity to changes in bond yields and therefore greater profits (or losses) from bond price movements, depending on which way yields move.

As bond yields have been falling over the past year, duration has been a strong tailwind for performance. However, that same duration risk can quickly reverse to cause losses if yields rise again. (details here)

With perfect foresight it would be easy to simply dial up or down interest rate risk to profit from fluctuations in bond yields. In reality, predicting the direction of interest rates is very hard to get consistently right because there are so many subjective variables and complex feedback loops involved. (details here)

Irrespective of which way you think yields may go from here, one inescapable fact is that as yields get close to zero, the risk vs. return trade-off from taking interest rate risk becomes asymmetrically poor. (details here)

When comparing fixed income investments, the amount of interest rate risk being taken can be assessed by the portfolio’s duration, which is a common metric disclosed in fund portfolio reports.

One might then ask the following questions when evaluating performance:

-

-

- Was interest rate risk a dominant driver of past performance?

- Is interest rate risk likely to be a headwind or tailwind for future performance?

- Where there is a heavy reliance on duration to drive performance, can a similar outcome be achieved more cheaply using a passive fixed income index?

-

What is credit risk?

In the same way that companies can borrow money via loans from banks, they can also borrow money from investors by issuing bonds in corporate bond markets. The interest rate that companies pay is typically (but not always) higher than what a government borrower would pay, which means corporate bonds usually offer higher yields than government bonds.

That additional yield is called a ‘credit spread’. In this case, the term ‘spread’ refers to the difference in yield between a corporate and government bond. Credit spreads represent additional compensation (i.e. higher yields) that investors demand in return for taking credit risk.

Credit spreads directly impact corporate bond prices because they reflect market perception of credit risk. When credit spreads decrease, corporate bond yields decline (assuming interest rates are unchanged) and bond prices rise.

The most obvious component of credit risk is ‘default risk’, which is the risk that a bond issuer fails to repay investors according to the terms of a bond. Corporates typically (but not always) have higher default risk than governments and therefore investors demand additional compensation to invest in corporate bonds.

However, there is more to credit spreads than just default risk alone, which is an important point in understanding why credit risk is highly correlated to equity risk on the downside. (details here)

While corporate bonds are the most easily accessible way to add credit risk to a fixed income portfolio, other types of fixed income investments can also carry material credit risk (e.g. RMBS, ABS, loans, EM debt). We can group them all together under the ‘credit investments’ label to differentiate them from high quality government bonds, which have negligible credit risk.

A fixed income portfolio can therefore take more credit risk by holding a larger proportion of credit investments. There are then two mechanisms by which increasing credit risk may increase the returns of a conventional fixed income portfolio:

1. Higher yields

As credit investments typically offer higher yields than government bonds, the yield of a portfolio can be increased by holding a higher proportion of credit investments.

The trade-off between additional yield vs. credit risk varies in attractiveness over time and across different market segments. (details here)

2. Price movement

More credit investments means more exposure to changes in credit spreads, and therefore greater potential for profits (or losses) depending which way credit spreads move.

As credit spreads have been declining over the past year, credit risk has been a strong tailwind for performance. However, that same credit risk can quickly reverse to cause losses if credit spreads rise again.

When comparing fixed income investments, the amount of credit risk being taken can be assessed by the portfolio’s allocation to credit investments and its credit rating composition (i.e. a large allocation to ratings below A- suggests material credit risk), which are commonly disclosed in fund portfolio reports.

One might then ask the following questions when evaluating performance:

- Was credit risk a dominant driver of past performance?

- Is credit risk likely to be a headwind or tailwind for future performance?

- Where there is a heavy reliance on credit risk to drive performance, can a similar outcome be achieved more cheaply using a passive fixed income index?

What is liquidity risk?

Liquid securities are those that can be readily bought or sold in sufficient volumes, at reliably transparent prices and without incurring punitive transaction costs. Illiquid securities are those that fail to meet these criteria to varying degrees.

Illiquid securities may carry more risk, not just because they are harder to sell but also because there may be less confidence about their market valuation. (details here)

Even long-term investors value liquidity in order to maintain flexibility of asset allocation or access to cash and those needs are often greatest at times of market stress, when liquidity is most tested. For these reasons liquidity risk always needs to be accounted for when comparing investments.

The additional return an illiquid asset offers above a comparable investment that’s very similar in all aspects other than liquidity is referred to as the illiquidity risk premium. This is what investors earn explicitly for giving up liquidity.

The types of less liquid fixed income investments that offer an illiquidity risk premium includes loans, high yield bonds, securitised credit products and emerging market bonds. A fixed income portfolio can therefore take more liquidity risk by holding a larger proportion of these types of less liquid investments, and thereby harvest the illiquidity risk premium to increase returns.

When comparing fixed income investments, the amount of liquidity risk being taken can be assessed by the portfolio’s allocation to types of securities that are either completely illiquid to begin with (e.g. some types of loans) or can become illiquid in adverse market environments (e.g. high yield bonds).

One might then ask the following questions when evaluating performance:

- Was liquidity risk a dominant driver of past performance?

- Is the extent of liquidity risk appropriate given the role this investment plays in a broader portfolio?

The tricky thing about liquidity risk is that it tends to surface in adverse market environments, when most conventional investments might also be under pressure, and it’s often not obvious until it’s too late. Most vulnerable are fixed income portfolios that build up a mismatch between the daily liquidity they promise investors and the liquidity risk of the types of bonds and loans they hold. (details here)

Implications for portfolio construction

The underlying risk and return drivers of a fixed income investment have important implications for how that investment can be used as part of a broader investment portfolio.

A key consideration is how the conventional fixed income return drivers discussed in this article will behave in different scenarios and interact with the equity type risks that dominate most investment portfolios. Most importantly, will they end up being risk reducing or risk additive in scenarios where equities perform badly?

For example, a common assumption is that interest rate risk diversifies equity risk and therefore adding interest rate duration to a portfolio should help improve overall portfolio performance in scenarios where equities incur losses. This works very well at times but becomes less reliable when interest rates are already very low to begin with or when there is heightened uncertainty about central bank policy actions. (details here)

It is also often assumed that any investment labelled ‘fixed income’ or ‘bond fund’ will be defensive in scenarios where equities incur losses, but that assumption doesn’t always hold. For example, credit risk may be uncorrelated to equity markets in benign environments but can become highly correlated to the downside. This means that credit risk, as a fixed income return driver, can become highly risk additive when equities fall materially and therefore credit investments actually carry a high degree of latent equity beta. (details here)

The common link between the interest rate and credit risks that drive conventional fixed income returns is that they are impacted by the same macroeconomic factors that also heavily influence equity market performance.

At times these macroeconomic factors impact them in different ways but at times they can all be affected in a similar way, resulting in highly correlated performance. This is what happened in 2018, when the US Federal Reserve raised interest rates, causing duration heavy government bonds, credit investments and equities to all incur losses at the same time.

There are however other less well-known fixed income return sources that are not directly driven by macroeconomic factors and can therefore provide consistent portfolio diversification benefits. They are also not dependent on the level of yields or direction of interest rates and can therefore provide consistently attractive returns, with low volatility. (details here)

An additional consideration for active fixed income funds is to differentiate between performance for which it is worth paying an active management fee vs. that which is largely driven by market factors and can therefore be replicated with cheaper investments such as passive index tracking funds.

For example, to justify a higher active management fee it is reasonable to expect that a portfolio with similar interest rate and/or credit risk characteristics to passive indices should consistently outperform those indices, particularly when those indices incur losses.

By contrast, if a portfolio is generating higher performance than those passive indices but doing so by consistently taking more interest rate or credit risk, it’s questionable whether that is worth paying more for. However, a portfolio with lower returns than those indices may still justify a higher fee if it’s delivering those returns with consistently lower risks.

Perhaps the most compelling example of genuine fixed income alpha is a portfolio whose performance is not driven by conventional fixed income return sources and therefore cannot be reliably replicated using passive investments.

Whether investing in active or passive funds, the best defence against the risk of nasty performance surprises is to look beyond headline return numbers and question the underlying drivers of performance, understand how they can behave in different market environments and how they might interact with other types of investments in different scenarios.