The bizarre world of negative interest rates

In an episode of the hit sitcom Seinfeld, when perennial loser George complains that every decision he has ever made was wrong and that his life is a failure, his friend Jerry convinces him that “… if every instinct you have is wrong, then the opposite would have to be right.”

George then wholeheartedly embraces this new ‘opposite’ philosophy and proceeds to do the exact opposite of everything he would normally do, excitedly proclaiming “I did this opposite thing last night. Up was down, black was white, good was bad”. He even takes to introducing himself to prospective dates in a novel way – “My name is George. I’m unemployed and live with my parents.”, resulting in unexpected success.

It appears that some central banks are following George’s lead in pushing monetary policy into the upside down world of negative interest rates, but rather than success they are creating bizarre side effects.

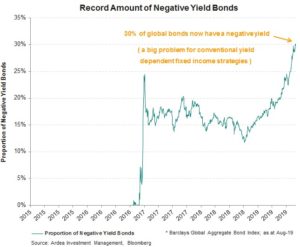

As the chart below shows, an astonishing 30% of bonds in the most widely followed global bond index now have a negative yield (44% excluding US bonds).

These side effects are now increasingly spilling over from financial markets into the everyday financial transactions that people engage in. For example, Jyske Bank in Denmark this month started offering customers 10 year residential mortgages at a negative 0.5% interest rate and Swiss bank UBS announced that deposit accounts holding over SFr2m would incur a negative interest rate of 0.75%, forcing customers to pay them for the privilege of depositing money.

They are even spilling over into the political arena, with German right wing populist group AfD claiming that negative interest rates are a European Union conspiracy that forces German savers to subsidise ailing southern European economies.

Beyond these bizarre side effects, the era of negative rates challenges core economic concepts like the ‘time value of money’. This is the fundamental idea in economic and finance theory that a rational person values a dollar today more highly than a dollar in the future because the dollar today has utility value. It can be used for consumption or invested to grow its value. This concept underpins everything from discounting cash flows when valuing stocks to explaining the rationale behind paying interest to borrow money.

The prevalence of negative interest rates turns this concept upside down. For example, it might suggest that if offered $10 today, the rational response would be to politely offer thanks but request that same $10 be given not today, but far in the future.

One explanation (from a different economic theory) is the idea of negative time preference. Conventional theory assumes people have positive time preference, meaning they value consumption today more highly than deferred consumption in the future and therefore need to be incentivised by positive interest rates to save money for the future rather than spend it today.

However, in modern advanced economies where people live longer and therefore face the prospect of long retirements, they may be more willing to sacrifice today’s spending and save for the future, even if the rates of return on those saving are very low, or indeed negative.

Another theory is a shifting demand / supply balance between saving and investment at the economy wide level. The theory goes that ageing populations and longer life expectancy, combined with technological advancement reducing capital requirements, means the demand for savings far exceeds that for investment. Hence there is a growing surplus of capital looking for a home, which is pushing the equilibrium rate of return on capital (i.e. interest rates) lower and lower.

While both these theories may explain zero interest rates, it seems too much of a stretch for them to explain materially negative interest rates, where savers are explicitly penalised for saving. This is like assuming that because retailers are willing to clear surplus stock by discounting prices, if the surplus gets large enough, they would be willing to actually pay customers to take the stock off their hands.

Debates about economic theory aside, the real world effects of negative interest rates are becoming increasingly clear. They cause distortion of risk pricing and lead to misallocation of capital.

Distorted risk pricing

In conventional fixed income investing there are two drivers of risk and return – interest rate duration and credit risk. Investors accumulate portfolios of bonds to harvest yield and earn a return in exchange for taking some combination of these two risks.1

As interest rates and bond yields have collapsed globally, fixed income investors have come under intense pressure to find ways to boost returns, triggering an immense ‘reach for yield’.

A wall of money has been progressively moving into riskier and riskier assets in search of higher yields, creating an environment in which the desperate search for returns trumps considerations of the risks being taken to earn those returns and whether those risks are being adequately compensated.

While negative interest rates and bond yields are not new, they are now seeping into longer dated bonds, as well as bonds issued by lower credit quality issuers. In doing so they are severely distorting pricing and eroding away any remnants of compensation for the duration and credit risks that dominate conventional fixed income portfolios.

Tackling duration risk pricing first, bond yields can be viewed as a cushion that protects investors from capital losses if yields were to rise (i.e. duration risk) and normally, investors would demand higher yields in return for taking more duration risk. However, as yield chasing capital has flooded into longer maturity bonds to eke out a bit more return, compensation for interest rate duration risk has eroded away.

The chart below shows the rising duration risk vs. the vanishing yield cushion of the most widely followed global bond index. The trade-off between the yield and duration risk has been deteriorating, leaving conventional yield dependent investors facing more risk for less return.

Hiding beneath index level averages like this are more egregious examples of distorted risk pricing.

For example, this month the German government became the first bond issuer ever to convince investors to buy 30 year bonds that pay zero interest. In fact, the bonds priced with a negative yield of -0.11% meaning that lenders (i.e. bond investors) are actually paying the German government to hold onto their money for the next 30 years.

To put the extent of pricing distortion in perspective, this bond carries so much duration risk that just a 1% increase in bond yields, which is where yields were as recently as October last year, would result in a capital loss of 32%. Yet investors are still willing to accept a negative return from owning this bond.

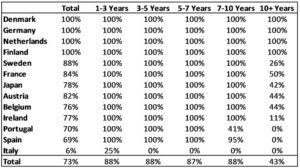

More broadly across European government bond markets, the table below shows four countries now have negative yields on 100% of their bonds. Even Spain and Portugal, which just a few years ago were at the centre of the Eurozone debt crisis, now have most of their bonds with negative yields.

Proportion of Negative Yielding Bonds Source: JP Morgan, Flows & Liquidity, August 2019

Source: JP Morgan, Flows & Liquidity, August 2019

High quality government bonds are widely assumed to be ‘safe’ investments and in terms of credit default risk that assumption holds. However, they are now highly risky in terms of the potential for near term capital losses if yields were to rise again.

While there is legitimate debate about whether bond yields will keep falling, as they have this year or revert to rising, causing capital losses as they did for much of last year, it’s hard to argue that duration risk is being priced appropriately when a 30 year bond can have a negative yield.

Investors rushing to the perceived safety of ‘high quality’ government bonds, have careened headlong into the poorly compensated and treacherous territory of duration risk.

One theory to explain why investors are willing to accept such poor compensation for duration risk is that they are more focused on getting their capital back in the future i.e. they value ‘return of capital’ more than ‘return on capital’.

Viewed this way, negative yields on high quality government bonds can be thought of as a fee for storing capital ‘safely’, in the same way that we pay fees for the safe storage of other valuables.

Proponents of this view argue that rising uncertainty around the global economic outlook, geopolitical risks, the safety of banks etc. have created extreme demand for safe storage of capital, resulting in a ‘safety premium’ that manifests as negative bond yields.

There are two problems with this argument. Firstly, in the case of safe storage of most valuables, for example a safe deposit box, you are paying for physical space and security features, whereas the capital being ‘stored’ in a bond is just a string of digital ones and zeros. Secondly, if there is indeed such an extreme demand for safety across financial markets, how can this be reconciled with the fact that riskier assets such as equities are trading near record high prices?

This contradiction leads us to the other part of global fixed income markets where pricing of risk has been distorted by negative rates and the reach for yield … the pricing of credit risk.

As with duration risk, it is rational to expect that investors should be compensated for taking the credit risk inherent in bonds issued by lower credit quality governments and companies (i.e. corporate bonds).

Coming out of the 2008 financial crisis, large portions of global credit markets offered very attractive risk premia (extra return received for taking on risk) that meant investors were well compensated for taking credit risk.

Since then, the reach for yield has driven enormous flows of capital into credit markets and progressively eroded away this risk compensation. There is now little risk premia left in many parts of global credit markets, and in a growing number of cases not even any base line compensation for default risk.

Startlingly, it’s not just high quality government bonds that now have negative yields but also corporate bonds that carry credit risk.

For example, companies like luxury goods retailer Louis Vuitton and pharmaceuticals giant Sanofi have both issued bonds this year at negative yields, while Nestle this month became the first company to have a ten year bond with negative yields.

Admittedly, these are currently large companies with solid balance sheets and low risk of default but in an economic downturn or if company specific negative catalysts occur, that risk could increase markedly. This is why any rational risk pricing framework would require corporate bonds to offer positive yields to provide a buffer against these types of uncertainties. A lot can change with Nestle over the next ten years.

Even more alarming, negative yields are now spreading to bonds issued by companies with much weaker balance sheets and therefore more credit risk.

Europe is ground zero for this mispricing of credit risk as the ECB keeps pushing further into uncharted territory of negative interest rates and escalating bond purchases via quantitative easing.

In a recent article, Bloomberg news counted 14 so called ‘junk bonds’ with negative yields. These are bonds issued by companies with credit quality ratings too low to qualify as ‘investment grade’ because of their weak balance sheets and material risk of default.

“Central bankers hinting at more monetary stimulus have depressed yields so much that even some European junk bonds trade at levels where investors have to pay for the privilege of holding them.

The number of euro-denominated junk bonds trading with a negative yield — a status until recently associated with ultra- safe sovereign borrowers — now stands at 14, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. At the start of the year there were none.”

– Bloomberg News, ‘Sub-Zero Yields Start Taking Hold in Europe’s Junk-Bond Market’, July 2019

In reference to these extremes of distorted pricing Euromoney noted:

“It is hard to think of a more bizarre consequence of quantitative easing (QE) than negative yielding high-yield bonds. Indeed, it seems that the capital markets have entered their own Bizarro World, the comic book realm where everything is the opposite of what it should be.”

– Euromoney, ‘Bonds: From High Yield to Below Yield’, July 2019

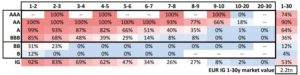

The table below from Deutsche Bank neatly summarises the absurdity of negative yields that has taken hold of European corporate bond markets, showing credit ratings of bonds across the rows and bond maturity buckets in the columns. 53% of the entire EUR investment grade bond market now has negative yields and even amongst junk rated bonds, 16% are negative yielders.

Source: Deutsche Bank, IG Credit Strategy, August 2019

They note the following:

“A new milestone has been reached: Just over half of the EUR IG market now yields less than zero, i.e. anyone looking to buy a EUR IG bond should know that a negative yield is the new normal.”

– Deutsche Bank, IG Credit Strategy, August 2019

Such distorted pricing dynamics become a self-reinforcing vicious cycle as yield driven investors like insurance companies and defined benefit pension funds are forced to buy anything that does not have a negative yield to avoid locking in asset / liability mismatches. They therefore chase after any bonds with a positive yield, irrespective of whether the inherent risks are priced appropriately, in turn driving those bond yields to zero and the cycle repeats.

This comment from strategists at BofA Merrill Lynch (somewhat depressingly) sums up the current situation:

“Following plunging global yields 10-year government bonds are now yielding -50bps in Switzerland, -25bps in the Eurozone, -12bps in Japan and +207bps in the US. How are you going to earn at least something in fixed income? Buy corporate bonds.”

– BofA Merrill Lynch, Credit Market Strategist, June 2019

For conventional fixed income investing approaches that are highly dependent on accumulating bonds for yield, sadly they are probably right. Buying corporate bonds, irrespective of whether the yield adequately compensate for the credit and liquidity risks that investors are being exposed to, may be the least bad option currently available.

These concepts around compensation for credit risk are explored in more detail here.

As a ‘reach for yield at any cost’ mentality has taken hold, sensible behaviour has been forgotten and the pricing of both duration and credit risk has become severely distorted. Reaching for yield by taking more risk can be a good option when those risks are well compensated but that is no longer the case.

What this brings to mind is a well-known Warren Buffett quote:

“What the wise do in the beginning, fools do in the end.”

Given the pressure on investment managers to increase returns in a negative rate world, the word ‘fool’ is too harsh. Perhaps ‘desperate’ is more appropriate.

Unintended consequences

The purpose of central banks cutting interest rates is to stimulate economic activity and when rates are cut from initially high levels, there is evidence that this desired outcome can be achieved.

However, there is a growing consensus that when rates get very low, the marginal benefit of continuing to cut further diminishes and the unintended negative consequences become more serious.

On this point, JP Morgan noted in a recent research report that negative rates may actually be having the opposite of their intended effect:

“In our conversations with clients the experiments of central banks with negative rates are viewed more as a policy mistake rather than stimulus and create a sense of an abnormal and uncertain environment that damages not only banks but also consumer and business confidence.”

– JP Morgan, Flows & Liquidity, August 2019

One unintended consequence is that yield driven investors such as insurance companies and pension funds are being forced into extreme risk taking behaviour:

“Pension World Reels From ‘Financial Vandalism’ of Falling Yields …

A once-unthinkable collapse in global bond yields is forcing pension funds to buy bonds that offer negative returns — putting the financial security of future retirees in jeopardy.”

– Bloomberg News, Aug 2019

A consequence of this behaviour is that conventional pricing relationships are losing their information value. The shape of yield curves no longer reflects the pricing of interest rate risk and credit spreads are no longer representative of credit risk.

Another unintended consequence is impaired bank profitability, which is a problem because a healthy banking sector is important for a thriving economy. (details here)

In cutting rates aggressively, as they are now doing, central banks appear to be undertaking a pre-emptive strike to prevent a sharp economic slowdown in future.

However, a growing body of research suggests that when interest rates are already very low, cutting them further or engaging in other forms of monetary stimulus becomes less effective in stimulating economic growth.

For example, a 2017 research paper from the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) noted:

“The empirical evidence relating to these questions is rather scant. That said, what is available suggests that monetary policy transmission is indeed weaker when interest rates are persistently low. The economic context appears to matter, making it more likely that policy may push on the proverbial string as headwinds blow.”

With interest rates and bond yields in most markets now at record low levels, and indeed negative in many places, the question for both bond and equity investors right now is whether central bank policies will have already hit their limits by the time they are really needed to get economies out of a serious bind.

Whatever your view on whether central banks are making a policy mistake, the implications for portfolio construction and the role that bonds are expected to play as part of a broader investment portfolio can’t be avoided.

The key takeaways are that ultra-low bond yields fundamentally change the risk vs. reward proposition of bonds and challenge conventional assumptions about how bonds behave. With the starting point of global bond yields already so low, the oft used disclaimer that past performance is not indicative of future returns is very relevant.

For those thinking about the diversification value of bonds in a broader portfolio, it’s important to look beyond labels and not simply assume that holding bonds is inherently defensive.

For those thinking about income generation, it’s now an inescapable fact that the two most widely used and long relied upon conventional fixed income returns sources – duration and credit – are offering more risk for less return than ever before.

However, as we continually tell our investors, there’s more to fixed income than just buying bonds. Even when yields are very low, there is a broader range of return sources beyond the conventional that can be accessed to generate attractive risk-adjusted returns, while also maintaining the defensive characteristics that are expected from fixed income investments.

1 Interest rate duration risk (measured in years) stems from the fact that bond buyers make a payment today in exchange for a series of future interest payments. At the time of purchase, the price of the bond will reflect the present value of that future stream of payments, which are fixed in advance. However, the next day if the general level of bond yields in the market rises, that fixed stream of interest payments is no longer as valuable, as it is now below current market rates. Therefore the bond would need to be discounted to attract new buyers, and the bond price drops accordingly.

The longer dated the bond (i.e. longer duration), the more future interest payments need to be discounted and therefore the more pronounced this effect. Hence, longer duration bonds carry more interest rate risk. As an example, a bond with interest rate duration of 5 years would incur a capital loss of c. 5% for every 1% increase in bond yields, while a bond with duration of 10 years would lose c. 10%.

Credit risk typically refers to the risk that a bond issuer fails to repay investors according to the terms of a bond (known as default risk). Corporates typically (but not always) have higher default risk than governments and therefore investors demand additional compensation to invest in corporate bonds.

However, there is more to credit risk than just default risk alone. Additional risk factors that need to be compensated include compensation for uncertainty, risk aversion, equity beta, funding risk, credit rating bias, fallen angel risk, recovery rates, tax effects, interest rate dynamics and liquidity risk.