November Rain – Implications of RBA QE for Investors

- In November, the RBA took monetary policy to new extremes by cutting the cash rate to near zero and embarking on a massive new Quantitative Easing program.

- Global developments still matter a lot for the Australian market, but RBA actions will limit the extent that long term rates can rise.

- Near-zero returns on cash and lower government bond yields will accelerate the reach for yield paradigm, exposing investors to greater risk.

- Cash alternatives such as relative value investment strategies offer returns well in excess of traditional cash, with low volatility and low correlation to equities.

The RBA’s November policy announcements

At its November meeting, the RBA announced a range of new policies to further reduce interest rates:

- a reduction in the cash rate target from 0.25% to 0.10%;

- a reduction in the target for the yield on the 3-year Australian Government bond to around 0.10%;

- a reduction in the interest rate on new drawings under the Term Funding Facility to 0.10%;

- a reduction in the interest rate on Exchange Settlement balances to zero;

- the purchase of $100bn of Commonwealth and state government bonds with maturities of around 5 to 10 years over the next six months.

What the RBA’s policy changes mean for investors

1) Near-zero returns on cash

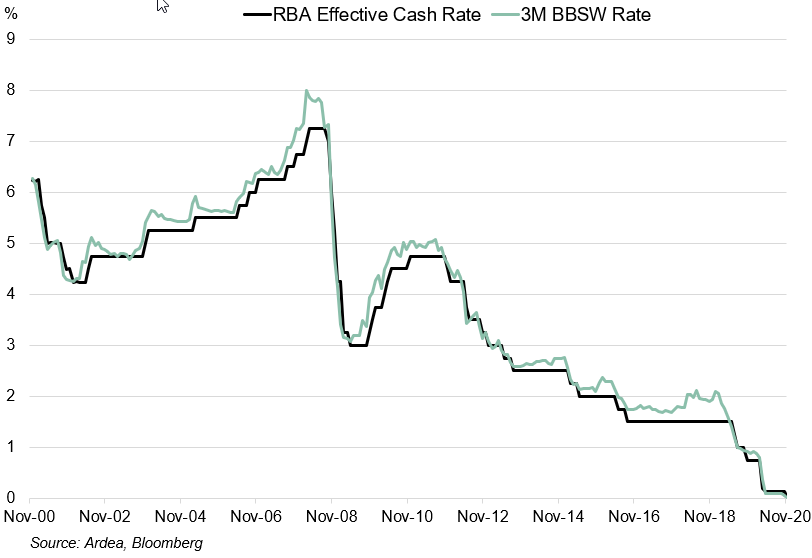

The RBA’s traditional policy tool – the cash rate target – is now at 0.10%. However, the interest rate on exchange settlement balances, which is basically the accounts banks have at the RBA, is now paying zero. The effective cash rate – the rate banks pay to lend to and borrow from each other – is settling lower than the 10bp target (currently 5bp). This leaves no more room for RBA policy to effectively lower the cash rate without making use of a negative rate policy. RBA Governor Lowe continues to suggest negative rates are “extraordinarily unlikely”. It is possible that the key short term market benchmark rate – 3m BBSW (currently 2bp) – could print at a negative yield due to excess RBA liquidity and supply/demand pressure in short term bank paper.

Chart 1: RBA cash and BBSW rates at record lows

2) Lower bond yields, but global developments still matter

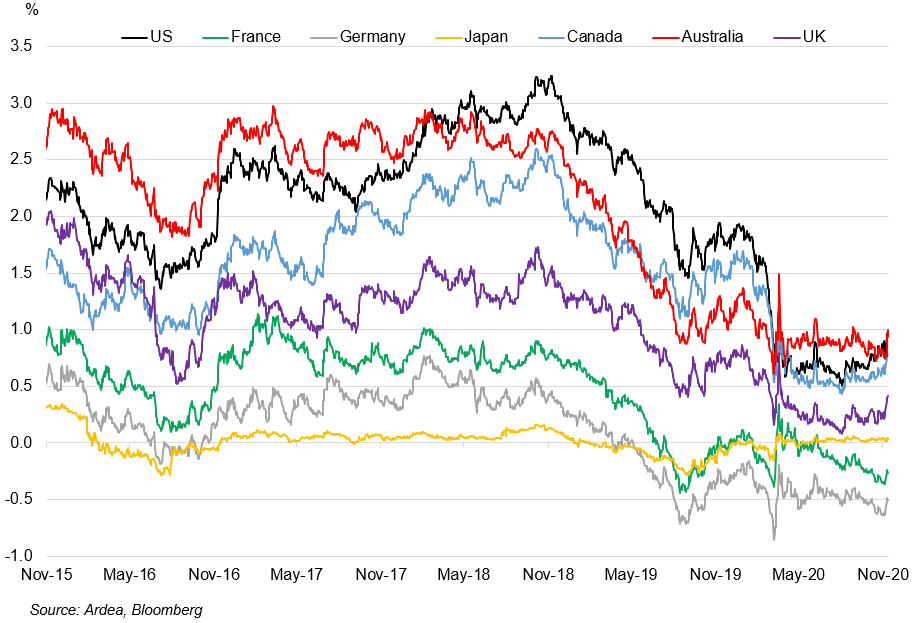

The new $100bn of RBA bond purchases over the next six months is large relative to the pace of Commonwealth and state issuance. The RBA is widely expected to take up most of the incremental supply of new government bonds. This supply/demand dynamic, as well as the signalling of future cash rates that this policy implies have contributed to lower government bond yields, at least relative to a scenario where policy was unchanged. Longer term yields are also at the mercy of global market developments. Since the RBA announcement, positive news on the prospects for a COVID vaccine has contributed to higher long term yields and the US election has also added to volatility. Going forward, since there is no explicit yield curve target beyond 3 years, there is likely to still be some up and down movement in Australian yields. But the RBA’s purchases should keep yields at a lower level than they otherwise could go and will limit the extent of future yield rises.

Chart 2: Global 10y government bond yields

3) Reach for yield behaviour will step-up another gear

Near zero returns on cash and a very low return outlook for government bonds will push many investors to take increased duration and/or credit risk to achieve an acceptable return. This strategy can add value while market conditions are supportive, but it also carries increased risk.

We have written previously about the asymmetric risks that come with the current market structure of longer duration bond indices and lower yields (see here for more detail). The key conclusion is that the global bond market is now more sensitive than ever to the risk of rising yields and the potential for further capital gains from falling yields is constrained. This is a significant trade-off facing traditional buy and hold government bond strategies.

The low rate environment has encouraged a significant increase in credit allocations. There is, of course, a place for higher risk credit within a broad portfolio. However, for the defensive and cash components of portfolios investors need to be wary of the illiquidity, equity beta and downside volatility risks of credit investments (see here for a more discussion on liquidity risks).

4) Cheap money for banks and governments

By increasing the size and duration of purchases of federal and state government bonds, the RBA is lowering the borrowing costs for federal and state governments in a key issuance target zone. Cheaper borrowing will help drive increased capital spending and pandemic support measures, as well as lowering the cost of servicing the massive deficits and stock of government debt. The lower market yield structure will also flow across the spectrum of borrowers, including corporates and banks. The banks will get an extra funding cost reduction in the form of a term funding facility rate of just 0.10% – at the time of writing this is slightly lower than the yields on equivalent maturity state government debt.

5) The (near) end of Australian monetary policy exceptionalism

In the decade preceding the COVID crisis, Australia stood out to global investors for its high cash rates (relative to periodic zero and negative rate policies elsewhere), relatively higher government yields, low government debt and importantly, lack of QE. In March, much of that yield and policy differentiation disappeared. Except that, by keeping a numerical 3y yield target and not conducting quantity-based QE, the RBA had helped reinforce relatively higher Australian government 10y yields and a much steeper curve than many peer markets.

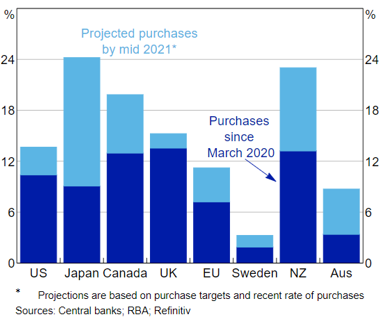

The Australian market will now look more like many G10 peers, since the 3y target remains but the RBA has moved into the realm of quantity-based QE. To be sure, there are still many nuances to QE across markets that make for significant cross-market variation. Australian ultra-long yields beyond 10 years are still elevated relative to peer markets and RBA purchases relative to GDP are smaller than in many other major economies (Chart 3). But the gap between 0-10y yields has recently compressed significantly, especially relative to the US.

Longer duration buying and quantity-based QE means the RBA has taken a big step towards the global central bank new normal. Therein lies a key issue – the Aussie dollar – a globally determined relative price which partly reflects global interest rate differences. RBA Governor Lowe hinted at the impact on the AUD in his November policy meeting remarks. While the RBA doesn’t explicitly target a level on the AUD, if they had sustained the prior policy set-up, capital inflows into the bond market could see the AUD trade higher, an unwelcome outcome that would make it harder to meet unemployment and inflation policy goals. Looking ahead, this sensitivity to the currency also means that investors cannot categorially rule out the possibility of negative rate policy, if that were to be pursued by more global central banks (especially the US Federal Reserve).

Chart 3: Central Bank Bond Purchases (% of GDP)

6) Monetary policy is pushing on a string

At the end of the day, the steps taken by the RBA in November will not be transformative for the economy. Monetary policy has always been a blunt instrument. But in prior recessions or crises, such as in 2008, rate cuts provided a powerful tailwind for the economy. That is no longer the case because interest rate and debt levels were already stretched heading into the COVID crisis. Moreover, a pandemic is a unique type of shock that presents policymakers with trade-offs between health and economic outcomes. The recovery requires massive, well calibrated fiscal policy spending. Fiscal outcomes have grown in importance for markets (see here for further discussion).

Alternative sources of return to cash and traditional fixed income

The zero rate and QE environment makes traditional cash and lower risk fixed income investments less appealing for many investors. Increasing allocations to credit or equities might amplify returns but will introduce significantly more risk to an investor’s portfolio.

Fortunately, there are alternatives that offer investors higher expected returns than cash, but with lower volatility and the benefits of diversification away from equities and credit risk. One such alternative is relative value fixed income investing. This strategy makes use of government bonds and closely related derivatives to generate low risk returns well in excess of low cash rates. This non-directional style of investment is not dependent on rates falling further or on a particular economic environment to generate returns (for more information on relative value investing, see here). In a recent research note, we showed that many relative value trading opportunities in global interest rate markets have increased since the COVID shock (see here).

This material has been prepared by Ardea Investment Management Pty Limited (Ardea IM) (ABN 50 132 902 722, AFSL 329 828). It is general information only and is not intended to provide you with financial advice or take into account your objectives, financial situation or needs. To the extent permitted by law, no liability is accepted for any loss or damage as a result of any reliance on this information. Any projections are based on assumptions which we believe are reasonable, but are subject to change and should not be relied upon. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Neither any particular rate of return nor capital invested are guaranteed.