Liquidity lessons from March

Liquidity, like the plumbing in your house, gets little attention until something goes wrong … and in March 2020 things certainly went wrong.

To be clear, illiquid securities are not inherently bad. They can be attractive when liquidity risk is explicitly recognised, well compensated and the time horizon of capital is appropriate. But problems arise when liquidity risk is underappreciated and creeps into portfolios that are intended to play a defensive role and are expected to remain reliably liquid.

The experience of March 2020, and prior episodes of market stress, remind us that portfolios with higher allocations to the credit segments within the fixed income asset class are most at risk of running into these types of problems. On this point, we previously noted:

“This liquidity mismatch between corporate bond funds’ underlying assets and the liquidity expectations of their investors has consistently grown over the past ten years. As a result, investors who had been reaching for yield in credit markets, thinking all is fine because default rates are low, may be unpleasantly surprised by how illiquid things become when they seek the exit.

In our view, growing illiquidity can become a major pain point for credit markets in coming years, so if you are going to take illiquidity risk, make sure it’s explicitly acknowledged and well compensated.”

This theme played out in a big way in March, when credit heavy portfolios suffered the double hit of falling materially in value and becoming illiquid. Many investors got a rude shock when these portfolios were forced to impose large sell spreads as their underlying bond and loan holdings became illiquid.

“A Morningstar report found that in the span of a few days in March, both passive and active managers including [XXX, XXX, …] had significantly raised the sell spreads on their bonds funds as it became harder for them to trade the underlying assets.”

– Investment Magazine, March 2020

The key takeaways from episodes like March?

- The credit risky segments of fixed income, including investment grade credit, can become completely illiquid in adverse market environments, while liquidity in core interest rate segments holds up much better.

- Multi-asset portfolio construction needs to look beyond labels and explicitly recognise the less obvious sources of liquidity risk in fixed income investments. Particularly in re-assessing liquidity expectations for credit heavy portfolios.

- Looking forward, investors should really be demanding higher illiquidity risk premia as a structural change to the way they evaluate all credit investments.

- Investors need to question how much liquidity risk is appropriate in a defensive allocation, considering that liquidity will be most challenged in adverse market environments, which is precisely when reliable liquidity from defensive investments is most needed.

Neither illiquid investments nor the credit risky segments of fixed income markets are inherently bad. It’s all about recognising their inherent risks, understanding how those risks might play out in different scenarios, assessing whether those risks are well compensated and thinking about the suitability of these types of investments in different parts of a broader portfolio.

While there is always a price for bearing liquidity risk, material liquidity risk may not be appropriate for the defensive part of a broader investment portfolio, no matter how attractive the returns.

Why should investors care about illiquidity risk?

Liquid investments are those that can be easily sold in sufficient volumes, whenever needed and without incurring punitive transaction costs. Illiquid investments are those that fail to meet these criteria to varying degrees. Liquidity is a spectrum rather than a binary concept.

Illiquid investments are not inherently bad. In fact, explicitly taking liquidity risk can be an attractive source of investment return. The additional return offered by an illiquid investment, when compared to other investments that are very similar in all aspects other than liquidity, is referred to as an illiquidity risk premium. This is what investors earn explicitly for taking liquidity risk.

Illiquidity risk premia are legitimate and potentially attractive sources of return, as long as the liquidity risk is explicitly recognised, well compensated and the time horizon of capital is appropriate. Problems arise when there is a mismatch between the true liquidity characteristics of the investment and the liquidity expectations for the capital being invested.

Episodes like March remind us that it is easy to take liquidity for granted until you really need it, and that need tends to be greatest in times of market stress, which is also when market liquidity will be most challenged.

These are also the times when multi-asset portfolios are most reliant on their defensive allocations to perform as expected, which is why it is so important to have a good understanding of the underlying liquidity characteristics of any investment being used to play a defensive role.

As this article notes, some fixed income investments failed to live up to their liquidity expectations through the March sell-off:

“Corporate bond funds have also upped their exit fees, lifting them from between 10 and 55 basis points to as high as 2 per cent.

The move comes to ensure that investors who are pulling their money out of the bond market aren’t leaving those who remain worse off and highlights the severe liquidity stresses in corporate debt markets that central banks are trying to rectify.

‘It’s fair to think that investors would have some expectation of being able to liquidate their bond portfolio without fear of incurring a major cost irrespective of the market conditions,’ said Morningstar’s Tim Wong.

‘And there are clearly instances where this is not the case.’”

– Australian Financial Review, ‘Bond market liquidity a problem says Morningstar’, March 2020

These types of liquidity failures pose practical problems for the investors in funds that have become illiquid:

Punitive redemption costs

In periods of market turmoil investors may want to redeem from these funds in order to rebalance their portfolios (e.g. buy the dip in equities) or simply because they need the cash. The imposition of large sell spreads becomes a hurdle to redeeming precisely at the time when investors may most need to do so.

Unreliable valuations

Liquidity (or lack thereof) plays a role in how confident you can be about an investment’s current valuation. As liquid securities are regularly bought and sold by many market participants, they incorporate a lot of information value in the prices at which they transact. This in turn provides confidence around the current market value of these securities and your ability to buy or sell at prices that do not vary drastically from this valuation.

By contrast, the price of an illiquid security is determined by infrequent transactions between a much smaller group of buyers and sellers, which in turn means the price you end up transacting at might vary significantly from the previous valuation, even if the broader market is unchanged. (details here)

For all these reasons, when comparing investments all investors need to consider liquidity risk and how liquidity characteristics might vary in different market environments. Even long-term investors value liquidity in order to maintain flexibility of asset allocation or access to cash, and that desire is often highest at times of market stress, when liquidity is most challenged.

Varying liquidity across fixed income

Within the fixed income asset class, liquidity varies dramatically across the different sub-segments and episodes like March remind us that the difference between the liquidity haves and the have nots can be stark.

Core interest rate markets sit at the most reliably liquid end of the fixed income spectrum. This segment comprises highly rated government bonds, related interest rate derivatives and highly rated money market securities.

Liquidity then progressively decreases and becomes less reliable for credit-risky securities such as corporate bonds, emerging market debt, loans and securitised investments, all of which can be harder to buy and sell. They tend to incur higher transaction costs and can become completely illiquid in adverse market environments.

Core interest rate markets have consistently evidenced superior liquidity through varying market environments and have done so for the following reasons:

Market size and turnover

Core interest rate markets are larger and have higher daily turnover than any other market, except perhaps FX. Their size and turnover are orders of magnitude larger than credit and even equity markets.

Regulatory support

Core interest rate markets form the plumbing of the global financial system and therefore receive much regulatory oversight and support. Reliable liquidity and functioning of these markets are essential to the broader health of the global financial system as well underlying economies.

Regulators and central banks in each jurisdiction have their own oversight and liquidity support mechanisms in place to ensure reliable liquidity and smooth functioning of core interest rate markets.

Diversity of market participants

The majority of flows (i.e. buying and selling activity) that take place every day across core interest rate markets are not profit seeking or speculative but rather, come from a diverse group of end users who have other objectives (e.g. risk management, regulatory requirements, policy objectives).

This diversity of end users supports reliable liquidity because it maintains a stable balance of buyers vs. sellers through varying market environments and ensures that securities are spread across a deep and diverse group of participants, rather than concentrated in a narrow niche of profit seeking market participants.

During periods of extreme market stress, such as the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 COVID-19 crisis, we consistently observe that liquidity in core interest rate markets holds up better and remains more reliable, compared to the credit-risky segments of fixed income markets. The latter can become completely illiquid, making it impossible for investors to reliably buy or sell bonds, loans etc. Even highly rated investment grade corporate bonds can become illiquid at these times.

Illiquidity creep in fixed income portfolios

We use the term ‘illiquidity creep’ to describe a growing proportion of less liquid securities within fixed income portfolios.

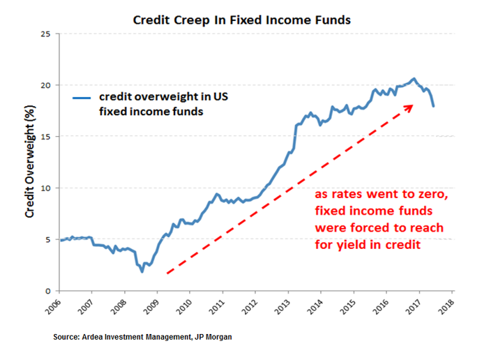

The warning signs of illiquidity creep had been building well before the turmoil of March 2020. In fact, this theme has been playing out for years as a side effect of another dominant theme amongst fixed income funds … ‘credit creep’.

With the dramatic decline of interest rates over the past decade, fixed income investors have been under intense pressure to boost returns. In direct response to this, many had been ‘reaching for yield’ in credit markets by persistently increasing their portfolio allocations to higher yielding credit securities (i.e. ‘credit creep’).

We previously discussed the ‘credit creep’ phenomenon here, where we noted:

“In the post-GFC era, corporate bonds have been a favourite sub-asset class within fixed income for yield hungry investors.

As a result, there has been a pronounced ‘credit creep’ phenomenon whereby even ‘defensive’ portfolios have consistently increased allocations to credit investments in search of higher yields.

This ‘credit creep’ has resulted in substantial overweight credit positions across many portfolios.”

While credit securities may offer higher yields in the good times, they also come with latent equity beta and illiquidity risks that surface in adverse market environments. (We previously discussed latent equity beta here)

The theme of illiquidity creep and hidden liquidity risk in fixed income portfolios is something we have discussed many times before, most recently here, where we noted:

“Most vulnerable to a future liquidity crunch are those running a growing mismatch between the regular liquidity they promise investors and the illiquidity of their underlying investments.

We expect to see more liquidity related problems surface as the desperate search for yield compels ostensibly liquid portfolios to keep pushing the limits.”

The most troublesome aspect of illiquidity creep is when material liquidity risk creeps into funds that are being used by investors for their defensive allocations, because it is here that expectations for reliable liquidity are highest. Investors expect to be able to redeem from their defensive fixed income funds at any time, without being hit with large sell spreads due to a funds’ underlying holdings becoming illiquid.

Unfortunately, the desperate search for yield has seen a growing proportion of fixed income funds head down precisely this troublesome illiquidity creep path.

“What’s really inside bond funds these days? The answer, for many of them, is more risk than there used to be.

With little fanfare, many traditionally safe investment-grade bond funds have been edging into more complex corners of fixed income. The goal: to eke out returns in today’s low-interest-rate world.

At issue is just how big some of those risks might turn out to be. Of particular concern is whether managers are moving into investments that could prove difficult to sell in the event investors rush for the exits.”

– Bloomberg News, ‘Bond funds drift into risky debt’, July 2019

Credit market liquidity problems are not temporary

The severe deterioration of credit market liquidity in March was not a one-off blip. It is now a structural feature of credit markets.

This structural change had been building since 2009 and, in our view was the most underappreciated risk amongst fixed income investors, particularly within the supposedly ‘safe’ investment grade corporate bond segment.

Liquidity in credit-risky segments of fixed income has deteriorated due to bank balance sheet constraints and other factors, which are long-term structural changes, not just a temporary blip. We covered this topic in detail here, where we noted:

“… it’s important to appreciate how structural changes in fixed income markets since 2008 have compromised liquidity in some parts of global bond markets. Unfortunately, it’s not always clear during the good times as to how badly liquidity can deteriorate when markets turn.

For example, within the defensive fixed income segment, the common assumption is that investment grade bonds are liquid. While this assumption does still hold for a specific subset of very high-quality government bonds, it is no longer true for a growing portion of the corporate bond sector (i.e. bonds issued by companies).

In fact, it’s widely underappreciated just how much corporate bond trading liquidity has deteriorated in the past ten years.”

We also previously noted, in reference to deteriorating credit market liquidity:

“This hasn’t yet been obvious because the sheer volume of yield chasing inflows to credit markets has provided an illusion of liquidity. It’s only when the inflows turn to outflows that the reality of illiquidity will become clear.”

And that’s exactly what happened in March.

A prudent corporate bond fund will always hold a cash liquidity buffer in order to facilitate redemptions, without being forced to sell bond holdings. This works in normal environments but in periods of stress (like March) they can burn through that cash buffer quickly, leaving the remaining investors with an even less liquid portfolio and forcing them to increase sell spreads on their funds.

Looking forward, investors should really be demanding higher illiquidity risk premia as a structural change to the way they evaluate credit investments. This applies to all segments of credit markets, but particularly to investment grade credit that was previously assumed to be liquid.

With current yields for investment grade corporate bond indices sitting in the 2-3% range, it seems there is barely any illiquidity risk premia being price in.

Implications for portfolio construction

Neither illiquid investments nor the credit risky segments of fixed income markets are inherently bad. It’s all about recognising their inherent risks, understanding how those risks might play out in different scenarios, assessing whether those risks are well compensated and thinking about the suitability of these types of investments in different parts of a broader portfolio.

While there is always a price for bearing liquidity risk, material liquidity risk may not be appropriate for the defensive part of a broader investment portfolio, no matter how attractive the returns.

For example, the defensive part of a broader investment portfolio is typically where investors need the most liquidity, particularly in adverse market environments. For example, the liquidity need might be to proactively rebalance the portfolio toward accumulating stocks that have cheapened, or it may simply be to fund unexpected cash requirements.

Either way, the defensive part of a portfolio tends to be the first call for liquidity, which is why material liquidity risk may not be suitable for defensive allocations at any price.

For investors used to relying on credit based absolute return or diversified bond funds in their defensive allocations, the experience of March is a reminder of how unreliable the liquidity of their underlying bond holdings can be. As such, this may necessitate a structural change in thinking about the way these types of funds are used as part of broader investment portfolios.

This material has been prepared by Ardea Investment Management Pty Limited (Ardea IM) (ABN 50 132 902 722, AFSL 329 828). It is general information only and is not intended to provide you with financial advice or take into account your objectives, financial situation or needs. To the extent permitted by law, no liability is accepted for any loss or damage as a result of any reliance on this information. Any projections are based on assumptions which we believe are reasonable, but are subject to change and should not be relied upon. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Neither any particular rate of return nor capital invested are guaranteed.