Conventional fixed income is not doing its job

Conventional portfolio construction assumes that governments bonds will diversify equity risk.

The theory is that when equities fall, bond yields decline, resulting in capital gains on bonds that help offset equity losses. The problem is that it’s not working that way in practice.

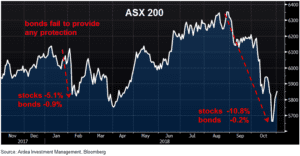

We’ve now had two instances in 2018 where the ASX200 had a material drawdown, and Australian government bonds also had negative returns.

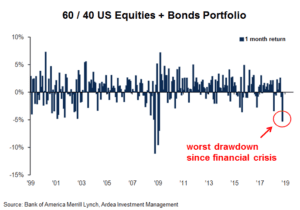

It’s even worse in the US, where the October drawdown of a 60/40 portfolio of equities and government bonds was the worst since 2009. Back then, the drawdown was large because equities fell a lot more, but now it’s because bonds are adding to equity losses.

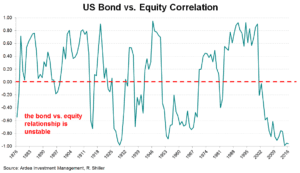

A longer history, as shown in the chart below, makes it clear that the relationship between bonds and equities is actually quite unstable.

It moves around because the bond-equity correlation – a statistical measure that describes the degree of relationship between rolling bond and equity returns – is sensitive to shifting interest rate and inflation paradigms, just like the one we’re seeing now. This is occurring as central banks, led by the US Federal Reserve, transition towards normalising monetary policy and signs of inflationary pressure have begun to emerge globally.

This type of paradigm causes the bond-equity correlation to shift from negative to positive, and we’ve already had a small taste of the consequences this year.

So why hasn’t the negative correlation assumption received much scrutiny?

Perhaps just because of short memories – since the 1990’s government bonds have benefitted from a secular bull market, which has underpinned the negative correlation thesis, but this is now changing.

While conventional bond holdings are perceived as an insurance policy to protect against equity losses, the reality is the policy may not actually pay out when you need it.

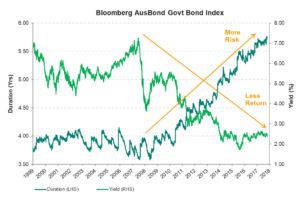

A further consideration is that government bonds are currently not cheap.

While there is legitimate debate about whether bond yields will keep rising, it’s hard to argue that bonds are cheap. This is because the trade-off between the yields you get compared to the interest rate risk you take (i.e. duration risk) is currently very poor. Duration risk arises from the inverse relationship between bond yields and bond prices – as bond yields rise, bond prices fall and vice versa.

The chart below shows the most commonly used Australian govt. bond index, which has seen duration risk increase to multi-decade highs, while yields have dropped to record low levels. In short, investors are getting more risk for less return. (for details refer – Low yields + rising volatility = a toxic combination for bonds)

This combination of record low yields and rising interest rate risk has left conventional government bond investments facing an uneven risk of capital losses from rising interest rates, with very little compensation in return … making them very expensive to hold.

There are certainly some scenarios in which conventional government bond investments will help buffer against equity losses. For example, in a classic recession scenario.

However, even in this case the payoff you get from holding bonds will be far lower than in the past. This is simply because interest rates (and bond yields) are already extremely low, and therefore have less room to fall further.

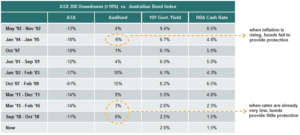

As shown in the table below, during the 2008 financial crisis the AusBond Government Bond Index delivered a gain of 15%, to help offset the ASX 200’s 61% drawdown. At that time, the RBA cut rates from 7.25% to 3.0% and the yield on a 10-year Australian government bond dropped from 6.8% to 3.9%, delivering large capital gains.

Given the current starting point for the RBA’s cash rate and 10-year bond yields, in order to repeat those capital gains the RBA would need to cut rates to -2.75% and 10-year bond yields would need to fall to -0.3%!

Source: Ardea Investment Management, Bloomberg

So even if bonds do perform as expected when equities fall, the payoff won’t be high.

On top of this, you’re currently getting paid very little to hold bonds relative to the rising interest rate risk you’re exposed to, making the implicit cost of holding bonds very high.

Tying all this together and viewing conventional bond portfolios as a form of insurance leads one to conclude that a) the cost is high, b) the potential payout is low and they may not even work when you need them most.

A poor value insurance policy from all angles.